Speculative Hydrology

Originally posted on STILLFLEET patreon.

Behold, this land.

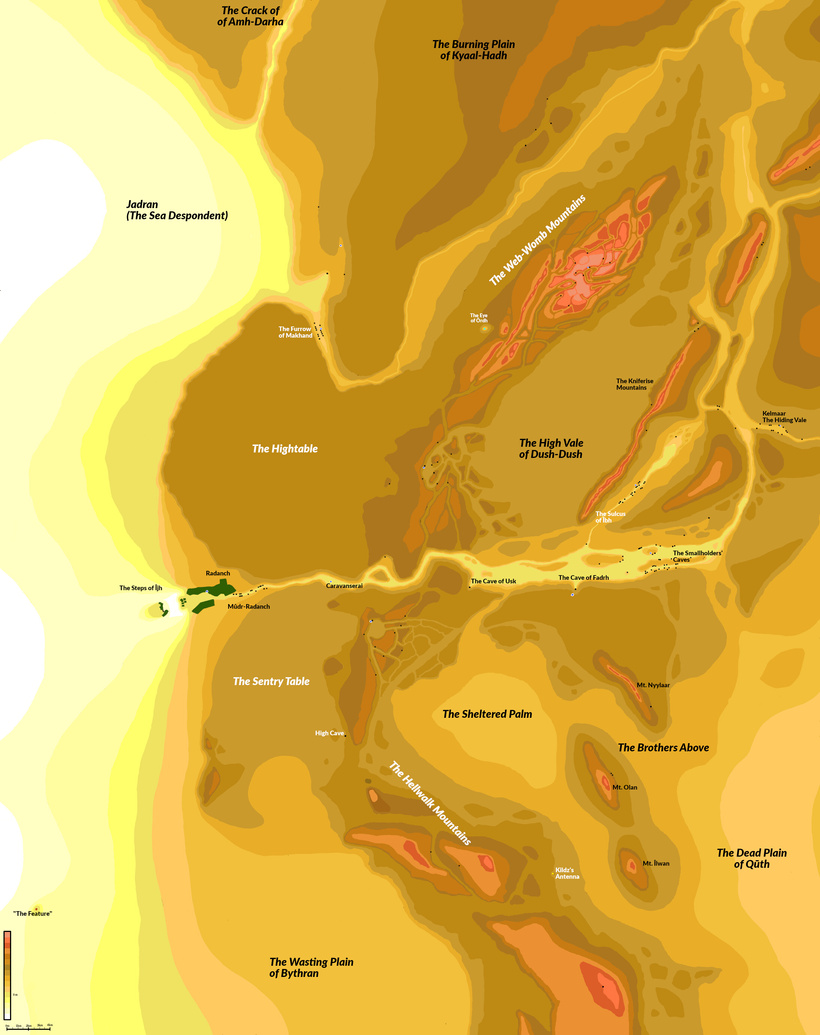

This is the current, and hopefully final, iteration of the map of the rocky desert planet, Radanaar, which is the setting for the new Stillfleet venture, The Rain Thieves. To scale, the area represented by the map is approximately 75 km wide and 95 km tall. Put in real-world terms, it’s roughly the size of the state of New Jersey, if you cropped the southern edge of the map to the latitude of Philadelphia/Camden.

A significant part of how this venture came to be is intertwined with the development of this map. There were countless times when I hit an impasse with questions like, “how long would it take a party to get from Radanch to the Eastern Sulci?”; or, “how much will Radasol [the local sun] heat this region throughout the day?”; or, “how steep is this canyon wall/mountain range/perilous drop?” The saying goes, “the map is not the territory,” but in this case it essentially is.

In the episode “Moral Worlds: The Meaning(s) of Fantasy Maps” of Jedd Cole’s podcast, Inside the Text, Cole differentiates the “description” and “prescription” of how a map interplays with the territory it portrays. The planet of Radanaar is obviously not limited to a New Jersey-sized excerpt, but this map circumscribes, as Cole puts it, the relevant portions for the setting of our new venture. I would even argue, the vast majority of the planet does not know that it is called “Radanaar” by the Co., so naming it Radanaar is an inherently political act: it prescribes the identity of the planet from the perspective of the human and wetan settlers, most of them Co.-originating. With settlements from two different immigratory origins, there is a question of linguistic origins: the settlers of the Eastern Sulci speak an Oud Carvolian dialect, whereas the more recent Radannais (living in Radanch) largely speak a dialect of Spin. Even in describing these peoples, who live mere dozens of kilometers apart, I cannot reduce them to a single collective title. The location names themselves are also all oriented from the perspective of an unknown, Spin-fluent Co. cartographer.

One of the origin points for Stillfleet is a trove of notebooks containing maps, tables, and descriptive passages that Wythe has written over the better part of a decade, perhaps longer. When I began writing The Rain Thieves, he sent me a high-resolution scan of the map he had drawn up for the one region of Radanaar known to the Co. He recently told me that the map’s genesis was partly motivated in getting the last bits of ink out of some markers that were beginning to run dry. The map is terrific! Beautiful desert mountain topography, a canyon or two, caves dotting the landscape, intriguingly named regions—it was already rich with content.

Pausing briefly from writing, I spent a weekend creating a contoured overlay in my photo editor. (Shoutout to the GNU Image Manipulation Project! Open source has a posse.) Even in simply adding lines to the map, I already had decisions to make: is this a steep edge here or a gradual one? Where is the edge of this surface? Is this change in elevation rising or falling?

Each decision writes a part of the geological history of this region. What is the story told in these mountains and valleys? This question has led to what we have jokingly referred to as “speculative hydrology.” The initial map that Wythe provided had winding canyons that seemed to strongly imply they were carved by water, now evaporated and absorbed—or perhaps removed?

In real life, at CE 2022 on Terra, I live in upstate New York in the Finger Lakes region. The Finger Lakes exist because, roughly 2 million years ago, during the Pleistocene Ice Age, a massive glacier covered most of what is now the state of New York. When the glacier retreated, the gashes it had previously carved into the crust filled with water and became the Finger Lakes. The deepest of these lakes, Cayuga, is 132 M (432 feet) at its deepest point! Over many millennia, tributary streams winding through the Cayuga Lake watershed slowly eroded many layers of sedimentary rock, creating the region’s famous gorges.

One waterfall in this region is Taughannock Falls. (Locally, they brag about it being taller than Niagara Falls; at 215 feet, it technically is 33 feet taller, though obviously Niagara has orders of magnitude more throughput.) Over a span of geologic time, Taughannock Creek etched away at the shale along the creekbed, running the debris out to Cayuga Lake. This process left behind a small canyon-like chasm roughly 100 M (300 feet) across and about 60 M (200 feet) high (though this varies in parts)—a gorge. It’s an absolutely beautiful area, and the creek is still slowly carving away, day after day. The gorge trail from the entry point to the falls themselves is a nearly 2 km-long mostly flat walk; the high canyon walls provide shade on one side or the other, depending on the time of day.

Taughannock Creek is not a straight line from the falls to the lake: it winds and curves around, the water always finding the path of least resistance. Since the easiest direction to continue carving is typically “down,” the shape of the canyon’s curves become more fixed over time.

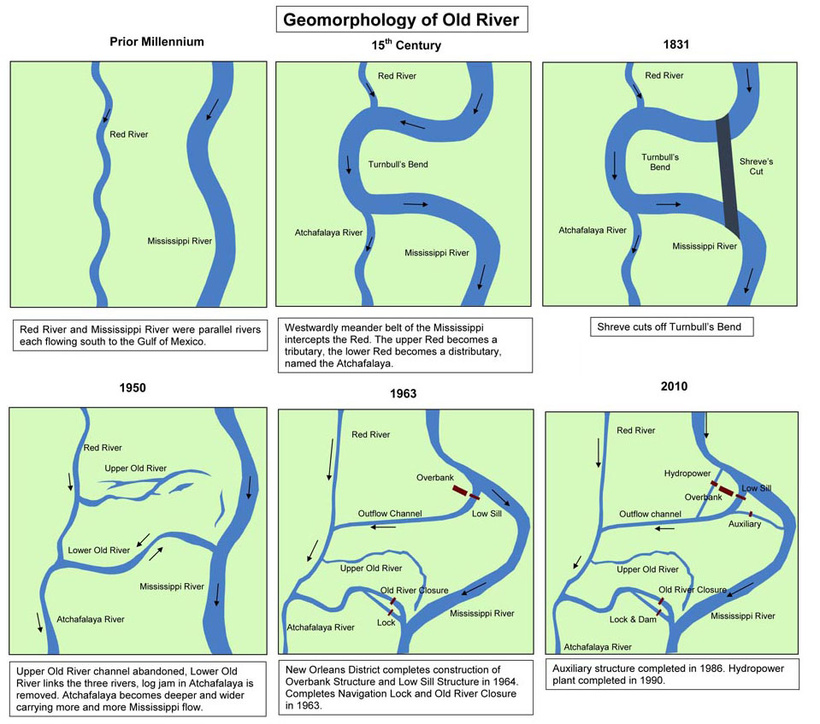

The book The Control of Nature by John McPhee discusses the history of the Mississippi River and its relationship with its sibling, the Atchafalaya. The Mississippi River and its smaller neighbor, the Red River, ran parallel for a long time. Around the 15th century, the Mississippi took a jog to the west and intercepted the Red River. The upstream portion of the Red River now fed into the Mississippi, and the downstream part of the Red River was now a distributary of the Mississippi, named the Atchafalaya. This new diversion was called “Turnbull’s Bend,” and it was about 32 km (20 miles) long. Centuries later, in the early 1800s, the bend increased travel times for steamboats, and so:

To reduce travel time, Captain Henry M. Shreve, a river engineer and namesake of Shreveport, Louisiana, dug a canal in 1831 through the neck of Turnbull’s Bend; this canal became known as Shreve’s Cut.

Additionally, the colonizers desired to maintain river-facilitated trade on the Mississippi via Baton Rouge—which is effectively below sea-level—without allowing for so much water to flow through that it would jeopardize New Orleans, further downstream. This whole region is simultaneously a massive feat of engineering and also evidence of our hubris to show mastery over nature. At the junction of the Mississippi and the “Old River” cross stream, connecting it to the Atchafalaya, is a complex of locks, channels, canals, and dams. The goal is to divert enough water from the Mississippi to preserve New Orleans, but not so much that the flow of the Mississippi is completely captured by the Atchafalaya.

Because, you know, it might affect trade.

While editing the map of Radanaar, the story that began to reveal itself through iterations was that there was some kind of water origin point in the northeast corner. Initially, it flowed southwestward, creating a canyon that ultimately yielded the Furrow of Makhand. Some time after that, though, it began to leak directly south, and found its way through the mountains just east of the Kniferise Mountains. I drew inspiration from McPhee’s telling of the Mississippi/Atchafalaya lore when bisecting this river’s flow: half of it ultimately bends eastward, creating Kelmaar, the Hiding Vale, and the other half, perhaps briefly, went westward, forming the channel that became the Sulcus of Îbh. Both branches fed into the primary canyon, which had long since dried up. Today (in the world of the game), it serves as the main channel for trade and commerce between the Eastern Sulci and Radanch.

I did my best to consider the order of how these individual diversions and redirections might have occurred, and how that would affect erosion depth as well as canyon width. I took some liberties to embellish new topographic features in the landscape: new mountain peaks, high elevation points, and additional smaller canyons all helped to tell a richer and more interesting geological and sociological story.

The southern half of the map, by comparison, was largely bereft of hydrologic eroding forces, and was instead shaped and formed by drifting sands, abrasive winds, and the burrowing of large xenofauna. The shapes of the landscape here are broader and more sweeping; the curves and elevation changes are less dramatic.

Near Radanch, the steep topography at what would have been the western point of exodus for the great canyon’s waters is colloquially known as The Steps of Ijh. Here, the water would have fed into Jadran (the Sea Despondent). I imagined a sturdy and resilient plateau that led to a waterfall digging down into the ground just west of Radanch. A rocky protrusion, sitting in the desert just west of Radanch, provided some shielding from the hot and abrasive easterly winds blowing in from the desert. I imagined that the early Radannais leveraged the lee of this protrusion to establish their “milk centipede” (galenoverm) ranches, as the galenoverms like to feed on microbes found in the soil, and the gap between these ranches and the city of Radanch seemed like an ideal place to snack.

On the pier-like escarpment, fully exposed to the sun, I imagined the Radannais would set up their sandclay foundries, fully embracing Radasol’s oppressive heat to bake their sandclay with skel’hūdūj (mat-forming microbes—one of the keystones to the entire biosphere on this planet) that is harvested from stuttercrab territory, south of the Sentry Table.

By comparison, the Eastern Sulci are more shielded from the blustery breezes of the desert and enjoy partial shade from Radasol for at least part of the day. Culturally, this would create an opportunity for climate arbitrage, and that led to differentiated commodities for each population. The “Separatists” of the east have a larger well-cave, and given the partial shade provided by the canyon walls, it seemed likely that they would probably capitalize on an indoor algae-growing operation. Because the raw harvested product, jaharn, requires additional heated preparation to make it consumable by humans, I inferred they would probably have some kind of elaborate lens-and-vat rig, concentrating the rays of Radasol that they did receive and focusing them on vats of unprocessed jaharn to catalyze its conversion to the comestible product, jaht.

Each settlement has played to its strengths, relying on one another to provide the things they cannot make so well themselves. This interdependence of the settlements informed decisions about the cultural interactions between them. When a voidminer asks a Radannais citizen, “where are your bandits?” the response is a somewhat confusing, “we don’t have any.” Forcible seizure of goods by either settlement would be too costly in attrition, and both settlements stand more to gain by allowing the other to exist as they are, rather than trying to impose their will upon them. Culturally, they both have different heritages—the few inhabitants of the Eastern Sulci are the original settlers (Carvolian immigrants who arrived via a Heechee stiffworks), set in their ways and living a more communal yet ascetic lifestyle. Radanch is more contemporary, having been settled in the recent past by the Co.—which later forgot about them. When faced with a razor-thin balance of survival, collaboration becomes awfully appealing.

The Caravanserai, labeled on Wythe’s original map, thus seemed like the optimal point of nexus for these two separate economic entities to intermingle. I inferred there would be a well here, because why else would people congregate here if not for fresh water? This reasoning then led to establishing the majority of the remaining wells. Essentially, anywhere there was an established settlement of living beings, I inferred that they would have chosen a location that had potable water. This included xenofauna!

The various populations of many-legged and massive critters congregate around sources of potable water. A few exceptions, the huldrathi and the stuttercrabs do not have a known, well-marked territory on the map, but a desert land has to have some secrets to discover, doesn’t it? My current headcanon is that the huldrathi spend the daytime buried in the sand; there, they somehow manage to absorb the moisture from underground. The stuttercrabs either have access to an unknown (possibly impotable) well, or they manage to gather moisture by snacking on skel’hūdūj near the High Cave near the Sentry Table.

Finally, there are the “spider” xenofauna. When imagining their lives, I focused less on speculative hydrology, but followed a similar line of thinking. The malgaunts and valebaiters are perhaps most analogous to what we might know as “trapping spiders” and “hunting spiders,” respectively. A trapping spider relies on its webbing to trap prey passively; a hunting spider relies on stalking its prey and disabling it with powerful venom. This called to mind an agrarian society versus a hunter-gatherer society in early human sapient history.

The malgaunts, settling near a well found among a small labyrinth of rocky formations between the Hightable and High Vale of Dush-Dush, lay traps in the surrounding areas and catch the occasional cragjumper goat, human, or wayward arthropod-like ghosteater. The calories found in a single human or wetan would almost certainly be enough to feed many spiderlike xenofauna for a while. (And malgaunt glands are used in medicines by the leeches in the Sulcus of Îbh, so the dance continues.)

By comparison, the valebaiters, living among the craggy rocks of the Web-Womb Mountains, actively hunt their prey. Their chromatophoric glands—which enable them to communicate via infrared shapes (think: heat-based emoji)—are prized by the hunters of the Eastern Sulci. During a recent playtest, a pir used the power aetherspeak to communicate with a nest of valebaiters. The responses they received were described as “Pusheen the cat, but as a spider, happily munching on a humanoid body.”

Designing this hellish, dry, horror-filled landscape has been an absolute delight. The 80ish pages of The Rain Thieves feel insufficient in fully exploring all the ideas I have for how this world works, but it is dense with passages from which an enterprising GM can derive their own stories. The new mini-venture using material from The Rain Thieves-“Motes in the Eye”—is secretly (don’t tell Wythe!) an effort by me to continue to feed my obsession with this planet, adding some additional rules and finding new ways to explore this beautiful buggy hell.

Underneath all of this work is a desire to allegorically explore themes of balance, justice, and ecological impact. Adding more content and detail further illustrates this delicate tapestry of survival. What happens when literally any of it is disrupted? What happens to the ecosystems in the Sheltered Palm if the Co. discovers rare metallic ore in The Brothers Above and sets up a mining operation? Even more innocently, what if the Co. wants to “help” the people of Radanaar by introducing new infrastructure? What if the people of the Eastern Sulci no longer depend on Radanch in mutual synergism? How will their cultures and societies be affected?

Radanaar is an artfully stacked tower of small-wooden-blocks, assembled for the sole purpose of letting you pull the blocks out, one by one—and watch the players try to put them back, or carve new ones. What new shapes emerge in the rubble, when it inevitably collapses? What will you do with The Rain Thieves?