Comparisons

One thing that has been so neat about this project is seeing when the translations appear to conflict, and thinking about what that means.

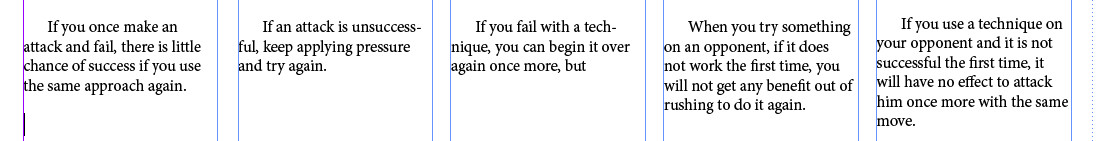

To try again or not try again

That’s Harris, Bennett, Tokitsu, Cleary, and Wilson, left to right.

| Harris, Cleary, Wilson | Bennett, Tokitsu |

|---|---|

| Trying again is probably not worth it. | Sure, give it a shot. |

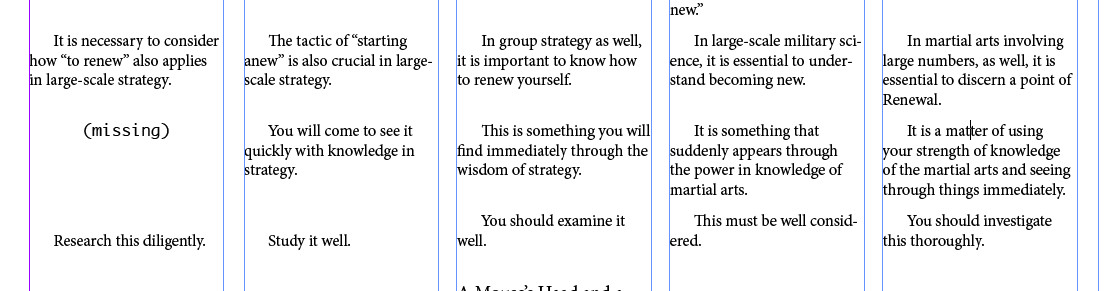

You must practice constantly

A common refrain at the end of nearly every passage in this book is some variation of “you must practice this constantly.” Agreed, Musashi! The funny thing is that each translator interprets it with completely different words, even though the connoted meaning is the same:

| Harris | Bennett | Tokitsu | Cleary | Wilson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research | Study | Examine | Considered | Investigate |

| Diligently | Well | Well | Well | Thoroughly |

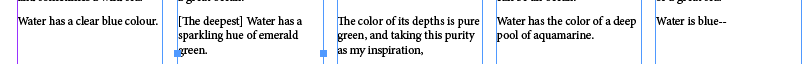

The color of water

This one is particularly cool. The disagreement about the color of water:

| Harris | Bennett | Tokitsu | Cleary | Wilson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| clear blue | emerald green | pure green | deep aquamarine | blue |

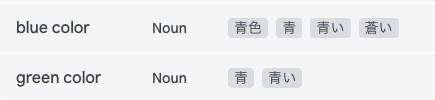

I talked with a few friends who spoke japanese about this. The [distinction between blue and green is apparently very subtle](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue%E2%80%93green_distinction_in_language#:~:text=The%20Japanese%20words%20%E9%9D%92%20(ao,green%20depending%20on%20the%20situation.)!

The Japanese words 青 (ao, n.) and 青い (aoi, adj.), the same kanji character as the Chinese qīng, can refer to either blue or green depending on the situation. Modern Japanese has a word for green (緑, midori), but it is a relatively recent usage. Ancient Japanese did not have this distinction: the word midori came into use only in the Heian period and, at that time and for a long time thereafter, midori was still considered a shade of ao. Educational materials distinguishing green and blue came into use only after World War II; thus, even though most Japanese consider them to be green, the word ao is still used to describe certain vegetables, apples, and vegetation. Ao is also the word used to refer to the color on a traffic light that signals drivers to “go”. However, most other objects—a green car, a green sweater, etc.—will generally be called midori. Japanese people also sometimes use the word gurīn (グリーン), based on the English word “green”, for colors. The language also has several other words meaning specific shades of green and blue.

In google translate, the word 青 translated into Japanese is blue, but translated into Chinese is green.

In the Japanese translation, both “blue” and “green” are under “more translations” and incorporate the same characters, as well.

Additionally, in the article about traditional colors of Japan, here are all the colors that incorporate 青:

| kanji | romanized | translation (wikipedia / google translate) | Hex color | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 青朽葉 | Aokuchiba | Pale fallen leaves / Blue decayed leaves | #AA8736 | ||

| 青白橡 | Aoshirotsurubami | Pale oak / Blue and white oak | #9BA88D | ||

| 青丹 | Aoni | Blue-black clay / Blue blood | #52593B | ||

| 薄青 | Usu’ao | Pale blue / Light blue | #8C9C76 | ||

| 錆青磁 | Sabiseiji | Rusty celadon / Rsuted celadon | #898A74 | ||

| 緑青 | Rokushō | Patina / Verdigris | #407A52 | ||

| 青竹色 | Aotake-iro | Green bamboo color / Blue bamboo color | 0,100,66 | #006442 | |

| 青磁色 | Seiji-iro | Celadon color / Celadon | #819C8B | ||

| 青碧 | Seiheki | Blue-green / Blue | #3A6960 | ||

| 緑 | Midori | Green / green | #2A603B | ||

| 青鈍 | Aonibi | Dull blue / Blue tin | #4F4944 | ||

| 群青色 | Gunjō-iro | Ultramarine color / ultramarine | #5D8CAE | ||

| 紺青色 | Konjō-iro | Prussian blue color / Navy blue | #003171 |

The “pale fallen leaves” one got me, in particular.

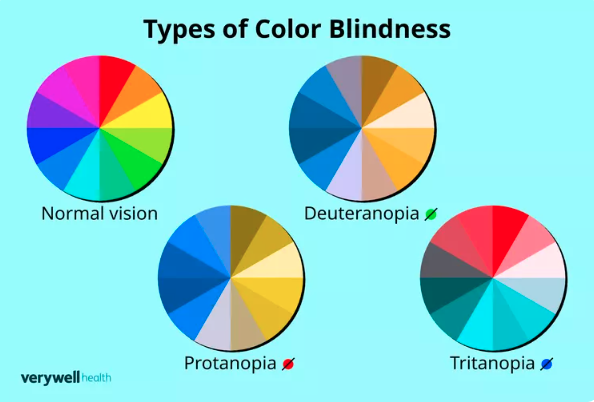

Since this color name wasn’t unique to just Musashi–this was a broader cultural definition–I started wondering “was a variant of color blindness really prevalent in Japan?” Cursory Internet searching says it is no more prevalent than Europe or other regions (though it does exist there). This chart in particular had me wondering:

Someone with tritanopia would see all of those colors as shades of the same hue (except “pale fallen leaves”, that one is an anomaly). I found a Pinterest board with a collection of “how people with tritanopia see the world”

This other blog post, titled Traffic Lights: are the Japanese color blind?, describes some of the etymology of ao:

These changing meanings of the same word in the distant past can be as fascinating as they are confusing. According to the oldest records of Japanese language, the words ao and aka (red) were associated with the idea of clarity. While kuro (black) meant darkness and shiro (white) meant light, ao and aka were in between, ao for a darker shade, and aka for a lighter shade. Kuro and kurai (dark) share the same etymological root; aka is linked to the word akarui, which means “clear”.

Similar color confusion is found in ancient texts from the Mediterranean regions (“bronze” colored skies and “wine-dark seas”).