Farsi Note Cards

Learning Farsi Script

Farsi has its own script, derived but separate from Arabic. Similar to Arabic, though, it’s also written right-to-left. There is no “print” version of the script (like how in English we have “printed” and “cursive”), just the script version.

I had started learning this a couple years ago, using some guides I got from my membership at Chai & Conversation. It’s a really neat language. There are 20-some letters, and a few modifiers that affect the vocalization of the letters (like a “b” sound turning into “bay” or “beh”) and most letters have initial, and/or medial, and/or final variants (depending on whether the letter is at the beginning, middle or end of the word), and each version has rules about whether it attaches on the left or the right.

From my prior experience learning some basic Japanese in my 20s, I was aware that things like stroke order and stroke form were important in writing the letters correctly. There are “right” and “wrong” ways, or at least “encouraged” and “discouraged” ways, to write these letters. I only had information about what the characters looked like, and some guesses about what it might be. The guesswork is based on the presumption that it’s written from right-to-left and the movement of the pen on the paper being continuous.

For xmas last year, my kids got me a book I was wanting that focuses on learning the script and, particularly, stroke order / form.

So on mornings where my language units are quick, or I only do review, I will spend some time working through a few of these letters. The book has workbook style spaces to practice the letters, but I will often also practice on lined paper as well.

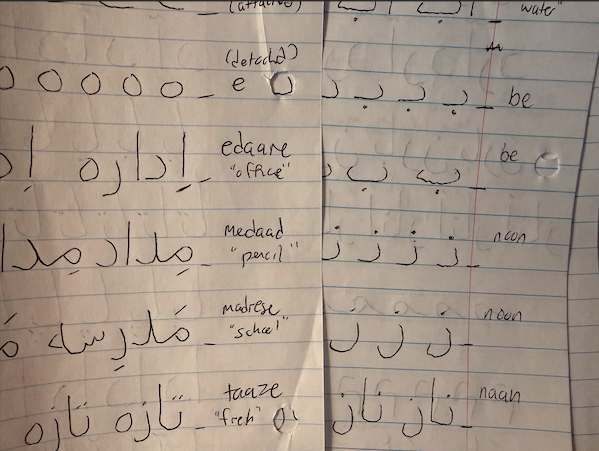

Practicing the script

One thing that has been challenging about this is knowing exactly where the “base” line should be. This isn’t always clear in the book text, and so sometimes I need to look at how the character is used in words, to see where the strokes are relative to others. Or how tall the letters should be!

In the image above, this is my best approximation and may or may not be correct!

For the use of the “e” diacritical (left side), the text was very clear that these go below the baseline, and are essentially the lowest part of the word. You can see in “madrese” (left side, 4th down) it’s lower than in “medaad” (3rd down).

If you can see how the letter “daal” (the leftmost character in “medaad”, it looks like a backwards “C”) and “re” (looks like a “J”) look similar, the main difference is that “re” goes below the baseline, whereas “daal” is very clearly above the baseline.

The relative height of the letters is also not always obvious. The letter “alef” (looks like an uppercase I, sans-serif, appearing twice in the word “edaare”), is “full height”, but is that twice the height of “daal”, or just 1/3 bigger? I imagine the precision here isn’t super important but it does make it challenging to know exactly how tall to make it on lined paper. Perhaps this would be clearer if I only had a single baseline and no median or top lines?

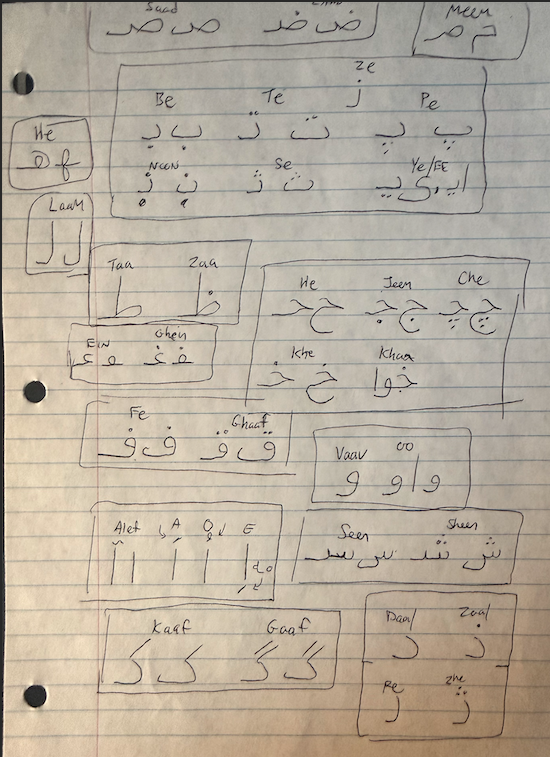

Grouping letters by stroke types

When I studied japanese, I remember that there were several different fundamental strokes (called “particles” in the book I was using), particularly in kanji, and that these were named and were reused. The index actually organized characters by which particles a character used, and how many strokes the character was.

VERY precise.

As I’ve learned the letters in the Farsi alphabet, I’ve noticed certain strokes get repeated. Sometimes the strokes are modified with one or more marks above or below the character (these are completely different alphabet letters), whereas other times it’s a normal character but voiced differently by the modifying mark (this is NOT a formally separate alphabet letter, just a different voicing).

I thought it would be interesting to group them by base stroke to see if any patterns emerged that might help a mnemonic. My thinking was “maybe the dot on top of the stroke acts as a reminder about how to voice the letter?”

Looking at “be”, “pe” and “ye / ee”, they all have dots underneath. The base stroke (like a squashed “u”) also becomes “te”, and “se” by adding dots above the strokes. It may be a stretch, but I could see how “be”, “pe” and “ye” feel like they sit more on the bottom of the mouth when voiced, and “te” and “se” sit more on the upper palate.

When I voice those sounds slowly, my lips close to voice “be” and “pe”, but my tongue moves up to voice “te” and “se”.

“ye / ee” kind of breaks this pattern (this sound sits a bit further back on the tongue), but also has kind of an irregular form.

With “daal” and “zaal”, the dot above the stroke for “zaal” seems to correspond with that same upper-palate feeling, like in “se” or “te”.

“Re” and “zhe” have similar mouth shape (say the word “mirage” slowly and feel the shape of your mouth for both the “r” and the “ge” sounds).

“kaaf” and “gaaf” are interesting – clearly similar sounds! The “kaaf” sound sits more in the front, near the teeth, and the “gaaf” sits just a little further back.

“Fe” and Ghaaf” look similar but feel the most dissimilar. Though “ghaaf” is especially interesting since this sound does not exist in English, so it’s a bit challenging to enunciate. My persian friend says it’s kind of like a “soft Q”. A video I found about pronouncing this letter says it’s involves the uvula and is a bit like the repeated sound your throat makes when you gargle. In Spanish, you roll the letter “r”, but making the tongue undulate in the middle of the mouth, this feels a bit like a rolling “g”, but only doing a single sound for it. It’s still challenging but I’m getting better.

In all, I don’t know that the dot placement is a very useful mnemonic, though the connection to how the letters are voiced is interesting. I will likely just need to practice reading and writing to familiarize myself with these.

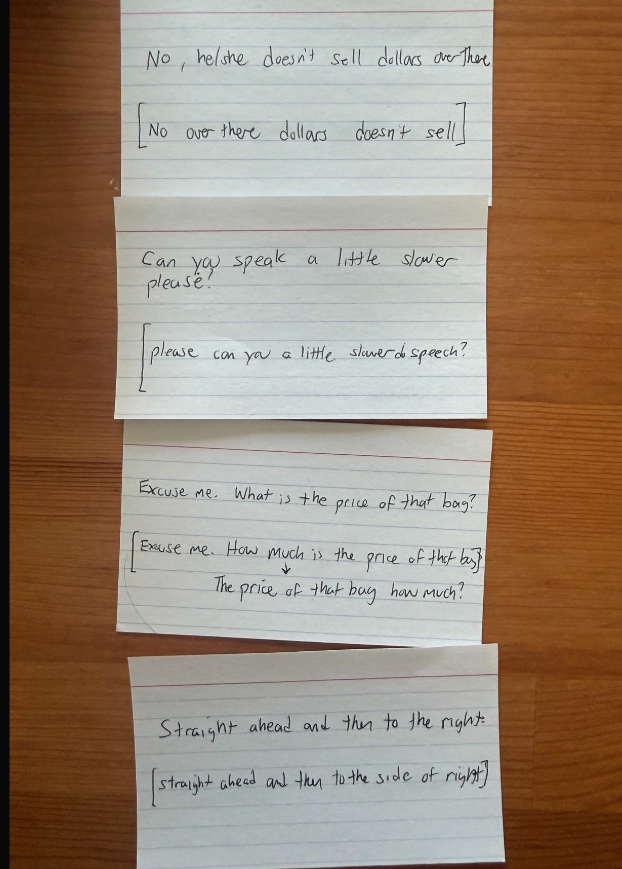

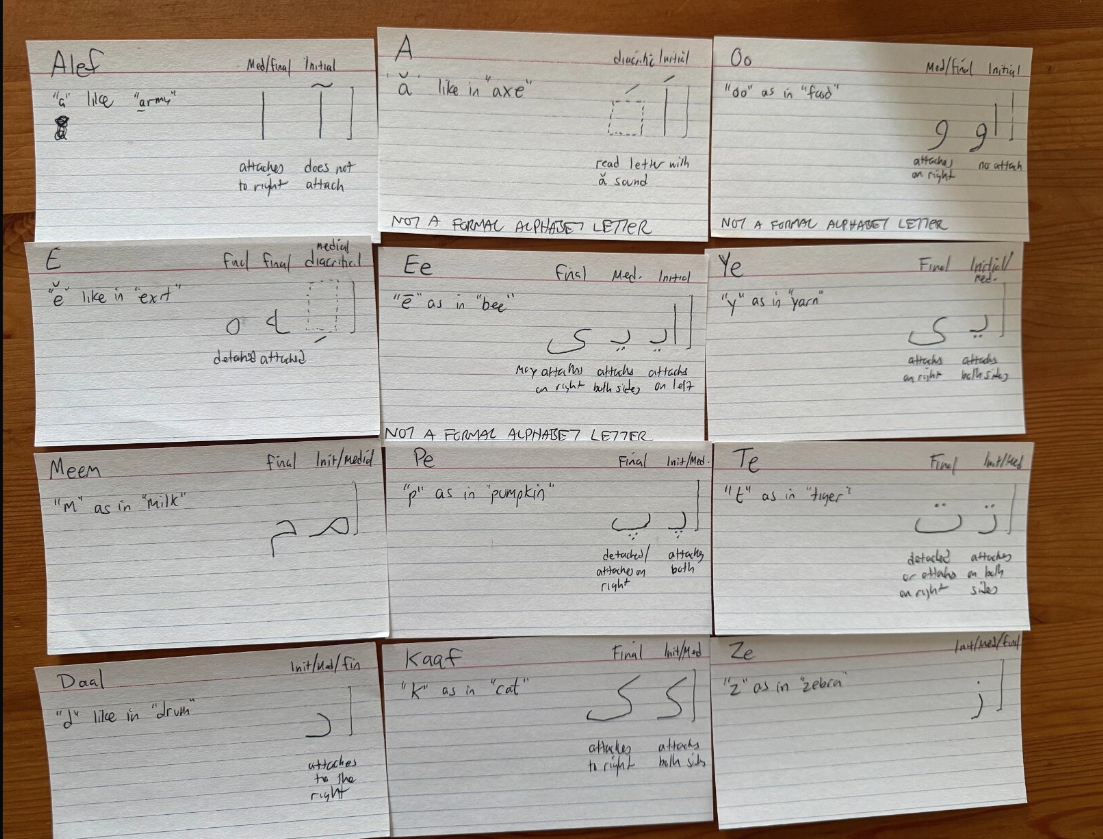

Here are some note cards I wrote down that I may use as flash cards, or just as quick reference cards, when reading.

Note cards

I’ve made some note reference cards for both individual characters, as well as some specific phrases and their literal translations, farsi spelling, and pronunciations.

The first two images show the English phrase, with the literal translation of the phrase below it (still in English) – this was meant to help me remember the word order, since Farsi grammar, similar to Japanese, puts the verbs last in a phrase, typically. So

Can you speak a little slower please?

becomes

Please can you a little slower do speech?

Some of the idiosyncratic phrasings, like “to the right” transliterating to “to the side of right”, are also helpful mnemonic indicators.

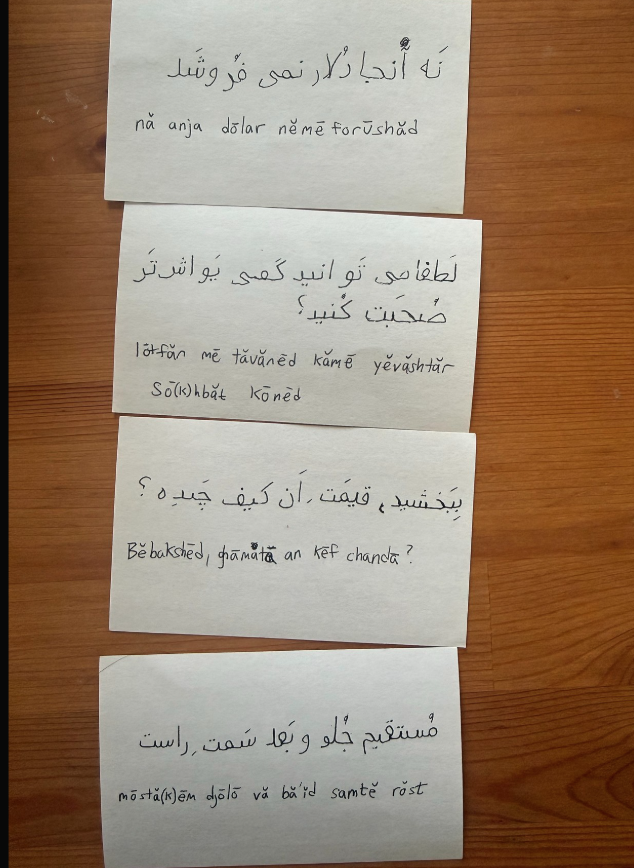

On the reverse (second image), I have the Farsi script translation (written right-to-left), followed by a Temu-brand-IPA-notation (it makes sense to me) on how to pronounce the phrase (written left-to-right, since the letters are romanized).

These are useful when I’m doing review. Sometimes I just need a small reminder about the word order, in particular. I’m still getting used to that.

Arabic Numerals

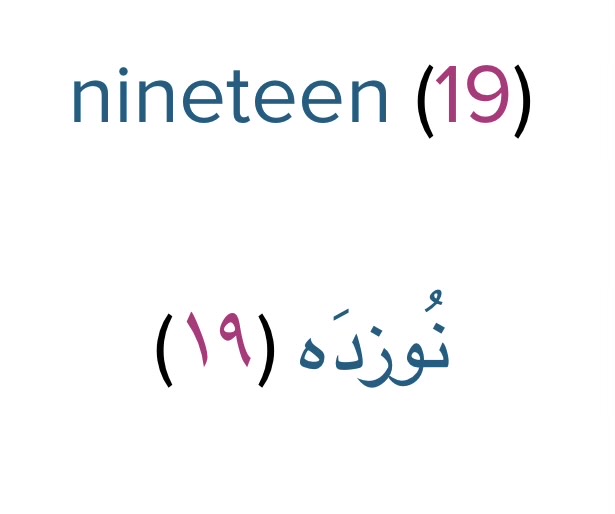

Lastly, I just finished the “counting to 100” unit. As you (hopefully) know, our own numeral system in English is based on Arabic numerals. Here is the number “19” (pronounced “nooz DAH”)

The lower half of the image is written in Farsi script, on the right with “noozdah” spelled out, and then on the left, in parantheses, as numerals.

To be fair, most of the numerals do not look exactly like our numerals, unless you rotated them, maybe; 2 and 3, rotated 90 degrees counter-clock-wise, ALMOST look like our numerals.

But this one specifically is pretty much dead-on. The stroke on the left is “yek” (1) and the stroke on the right is “noh” (9).

Interestingly, this stroke order both makes sense in a right-to-left writing schema (the numbers increase right to left), and in pronunciation, we say the “9” indicator (“nooz”) before the “10” indicator (“dah”).

In English, we do the same thing! We write “19” and we say “nine-teen” (reading right-to-left) and not “Ten Nine” or “Ten and Nine”.

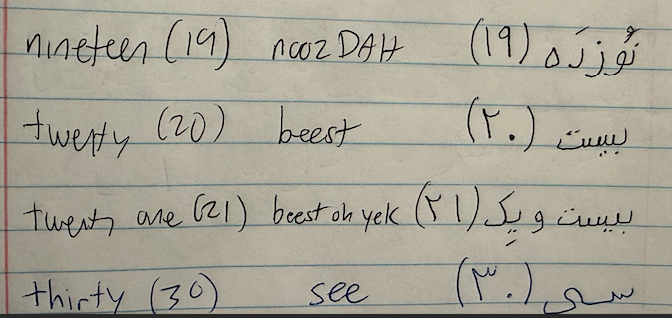

What gets really weird is that when you get past the teens and into the 20+ numbers, it takes on a more expected naming schema: “21” is “20 and 1” (“beest oh yek”), “56” is “50 and 6” (“panjah oh shesh”). The word “and” (normally pronounced “va”, is pronounced “oh” here, which looks similar but I don’t fully understand this yet).

So even though the language is read right-to-left normally, with numeral groupings, we read them left-to-right! “twenty and one” (left to right) and not “one and twenty” (right to left).

I’ve not gotten past one hundred, but my hunch is that the number “119”, one hundred nineteen” (first number, last number, second number) would be similar in Farsi: “sad oh nooz dah”. I’ve not gotten there yet, so we’ll have to see if I’m right. I don’t want to spoil it.